Concentration of Aging Homes in Lower-Income Areas Underscores Need for Mortgage Innovation

More than half of U.S. homes are over 40 years old and concentrated in minority or moderate- to low-income neighborhoods in urban areas, according to a recent Freddie Mac study that included most of the country’s single-family residences.

The study revealed the concentration of aging housing stock in lower-income communities where owners may not be able to afford maintenance and, for new buyers, the costs of major improvements.

With a better understanding of issues surrounding aging housing stock, lenders can help people in this situation with a type of mortgage that makes it more economical to either rejuvenate an aging property.

“Community preservation is inextricably linked to stability, and stability is reflected in the condition of the homes in a neighborhood,” said Simone Beaty, product development director for the Duty to Serve team in Freddie Mac’s Single-Family division.“The goal is for homeowners to stay in their communities by choice and for new buyers to be drawn to these areas, and that’s something traditional mortgages weren’t really designed for.”

A Deeper Dive Down to the Census Tract Level

The Freddie Mac study examined 2018 property tax records of 72 million single-family residences—about 90% of the country’s inventory. They ranged from detached houses to condos to factory-built homes, excluding only co-op apartment buildings. The study defined “aging” as homes built prior to 1979, when building codes and regulations began standardizing residential construction.

To understand the location patterns of aging housing, researchers focused on four cities and one state—Milwaukee, Chicago, Memphis, Omaha and Mississippi—all of which have wide homeownership gaps between minority and non-minority populations. They were also able to analyze in these places the amount of aging housing stock by minority and low-income census tracts.

Aging Inventory: Up Close in the Midwest, South and Great Plains

Out of the cities analyzed, Milwaukee had the highest amount of aging housing stock. Some 80% of the 176,358 homes sampled were built before 1979 and had a median age of 62 years. Most of this housing was built in the 1950s.

An analysis of 720,000 single-family residences showed 55% of them fell into the category of aging housing stock, with 41 years as the median age. New construction hit its highest point in the 1990s, amid gentrification in older neighborhoods. It edged slightly lower in the early 2000s, before collapsing in the 2010-2019 decade, a consistent trend among all four metro areas and nationwide, as a result of the 2008 financial crisis.

Half of the 398,421 units examined classify as aging stock in the only Southern city examined closely in the study. But the median age of these homes was slightly lower: 37 years. Researchers found that aging housing stock was heavily concentrated in older sections of the city, largely home to African-American residents with lower to moderate incomes.

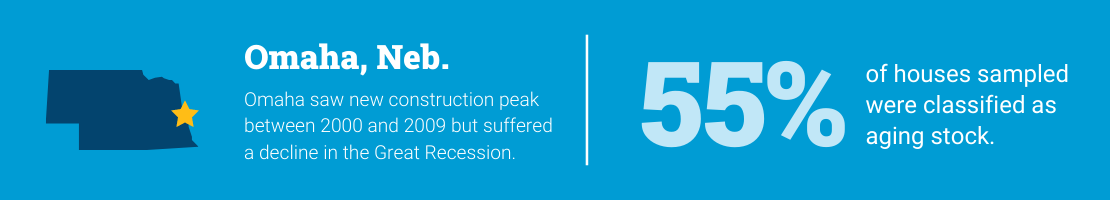

The smallest of the cities chosen, Omaha had 55% aging housing stock out of a sample of 261,404 residences. Like Memphis and Chicago, Omaha saw new construction peak between 2000 and 2009, but suffered much less of a decline in the Great Recession. Among the group, the city has the smallest African-American population, but also the greatest homeownership gap between its minority and non-minority communities.

Like several other Southeastern states, Mississippi has a relatively lower proportion of aging housing stock--47% and a median age of 35 years--based on a sample of 502,964 homes in urban and rural areas. One partial explanation for this is that manufactured housing makes up a large amount of single-family residences in the state.

High Cost of Home Improvements Poses Obstacle for Owners, New Buyers

While age doesn’t reflect a home’s condition, it usually translates into costlier upkeep and more safety issues, such as deteriorating roofs, faulty wiring or outdated plumbing. Homeowners often put off necessary work they can’t afford, making the property less livable over time and unattractive to future buyers.

A Bold Answer to an Age-Old Homeownership Problem

However, the industry has responded with a mortgage that’s big enough for low- to moderate-income borrowers to extensively renovate a home they want to remain in or buy and rehab a new one. They can also use it to shore up a home against natural disasters or build an accessory dwelling unit (ADU). The terms are more advantageous because the loan is based on the appraisal value of the home post renovations versus that of its current condition. That’s not the case with a typical home equity loan or cash-out refi.

When it comes to lending innovation and increasing homeownership, “You can’t just build your way out of this,” Beaty said. “You’ve got to value and preserve what’s already built and standing, which has anchored so many communities.”